The Farmer and the Fairy

By John French, 2024

Cwyndher the farmer let a tear fall over his cheek. Just one. It was the first tear he had shed in decades. He quickly wiped it away as he watched the two youths lower his wife’s lifeless body into the grave on the windy hill. For years that lovely woman kept their humble home in order. While he was away at war, she raised their daughter, Gwynette. She cared for him whenever he took fever, or had been injured, or was simply tired. She loved him, and he loved her. For all these reasons, he shed a tear for her.

Cwyndher the farmer put his hand on the hilt of his iron sword. He wore the sword, and the jewel encrusted belt it hung from, only for exceptional events. This was such an event. He straightened himself proudly and turned his head to the morning sun. The birds sang, oblivious of the sorrow and of the soul wrenching ritual taking place nearby.

The youths gently set his wife in the grave. They turned the lifeless lady so she faced the west, with her back to the east. Such was custom in these parts. Even in death, the lady was obligated to turn her back on the evil Dracii Mountains which towered in the eastern sky. The mountains were cursed and vile. Evil people roamed there, and often came out of the mountain castles to wreak evil havoc on the people of the plateau. Many wars had been fought over the centuries between the plateau people and those evil Dracii Mountain men.

Cwyndher the farmer dropped a poppy in the grave. The red flower landed lightly on the lady’s linen wrapped shoulder. Poppies were her favorite. She always had some in a vase at the dinner table. He nodded his head and the youths took their iron shovels and began pushing the soil into the hole. He said goodbye to her one last time as the dirt piled over her, shutting her off from the sunlit world forever. Then they laboriously slid a heavy stone slab over the dirt. The farmer bent down and helped them push. After the stone was in place, they all straightened up, panting.

“Were you a soldier, sir?” asked one of the youths.

“Heh?” grunted the farmer with an annoyed scowl. “Why do you ask that?”

The youth pointed to the farmer’s sword. “’Tis a fine blade. Not many people have the means to buy a sword. I thought perhaps you had been a soldier. Have you seen battle?”

“I don’t speak of it,” said Cwyndher curtly. He didn’t speak of it, but he thought of it, and more often than he’d like to. He remembered being a young infantryman on patrol in the foothills near the Dracii. Mountains. His patrol had intercepted a group of twenty armed invaders from the mountains. There was a short skirmish that left only nine of the vile mountain men alive. Cwyndher’s commander ordered the eyes of eight of them to be gouged out. The ninth survivor was to have only one eye gouged out so he could lead his comrades back to their hilltop castle to warn the other mountain devils. Cwyndher performed a gouging himself. He was shocked when the mountain devil cried out in pain and tried to squirm away from the blade. These were men after all, Cwyndher realized, like himself. The episode turned his stomach and wrenched his heart. For the remaining years of his military service, he killed all of his opponents. He never took prisoners. He appeared to be merciless, but he refused to subject a man to such tortures. He refused to be as evil as his enemies were.

“Sorry sir, I meant no harm.” the youth said.

The farmer nodded, and gave the youths each a silver coin for their work. The youths left Cwyndher alone at the grave. He sighed and looked around. The burial ground was on a high round hill and he could see the forested hills and castle towers in the distance with the occasional thatched rooftop and stone chimney peeking out from the green trees. He suddenly felt that the world was larger and lonelier than ever before. Burying his beloved was a hard thing to do, but now he had an even more heart wrenching task; he had to find their daughter, Gwynette and tell her that her mother had died. The beloved lady had suddenly fallen ill just two days ago. She had slept fitfully and feverishly through the night. In the morning she took a labored, gasping breath and died. Cwyndher the farmer had no time to find Gwynette before her mother had to be buried.

Cwyndher wasn’t even sure how to find his daughter. The previous summer, a small group of priests and priestesses had traveled down the River Daerhi looking for young men and women to tend the sacred wellspring and gardens of the Holy Grove. The holy people chose Gwynette, among other local girls, to learn the ways of the gods and goddesses of the Sacred Grove. What an honor! What an opportunity! Men and women struggled to survive in this wild and cruel world. If a girl could spend her youth tending to sacred gardens and eating at sacred tables and learning of sacred knowledge, a father would not have to worry about his child’s well-being. Her future would be certain. She would likely learn the ways of the priesthood, spending her life in the service of peace and love, not the war and hatred of Cwyndher‘s youth.

He allowed himself one more look at the great stone slab that marked his wife’s grave and turned away. He followed the winding, narrow path down the hill and into the canopy of trees. From there he took the narrow road north until he reached his farm. His house was a small stone-walled structure with a thatched roof squatting in a large vegetable garden. Beyond the house and the garden was a large grassy plot where two milk cows were grazing. He walked past the empty house to a stable and a chicken coop on the edge of the plot. He went in, gathered some eggs, a clay bottle of milk, some smoked venison, and a sack of oats. He then took his small pack horse named Merlod by her lead, and guided the animal out of the stable to the house.

Cwyndher went through the house quickly, not pausing to let the emptiness settle in his heart. He didn’t glance up at the loft where his bed was and where his love had passed away. He didn’t sit at the table where they had eaten and laughed together. He gathered up some jars for water, a long staff, a bone fish-hook, some twine, a blanket, extra shirts and coats, a pot and a frying pan, some lard. He packed it all carefully in a leather pack and slung the pack over Merlod’s back. He made sure the fire in the hearth was completely snuffed, and he walked out of his house. He went to his well and drew some water to fill the clay jars.

Turning south, he led Merlod down the road, walking past the trail that led up to the burial ground. He paused and gazed up the trail. He wanted to run up the hill to see if perhaps he had been dreaming, and perhaps she wasn’t really dead. But he knew she was. He’d held her until she went stiff. He knew death. Cwyndher sighed and walked on.

Around noon he came to the Holy River Daerhi. A wooden bridge had been built over the rushing stream. By ancient tradition, only an oak construct was suitable to span this sacred water. Stones came from the earth, as the water came from the earth. The river cut through and was guided by the stones in the earth. The stones could never be above the river unless the gods placed them there. Therefore, no stone bridge crossed the River Daerhi. Cwyndher took care to knock the dirt from his shoes, and from Merlod’s hooves before he crossed the bridge. It was wrong to let too much road filth fall into the sacred waters.

On the other side of the bridge was a crossroad. Cwyndher took the road to his right, heading upstream. He knew the river welled up from a spring, and the spring was in the sacred grove surrounded by great oak trees. If he followed the river to its source, he would be able to find Gwynette. He walked beside the babbling, bubbling river, leading Merlod along, until dusk. He stopped at a clearing and unfurled his blanket and made a fire. He ate some of his smoked venison and drank some water. Merlod ate a bit of her oats, but seemed more interested in grazing on the tender undergrowth along the road. As the fire died down, the farmer fell to sleep.

Cwyndher awoke just before dawn. He placed some kindling over the smoldering coals and the fire lit anew. He used his staff and some twine to cast a worm on a bone fishhook into the river. He caught a river carp, cleaned it, filleted it, and cooked it in his frying pan with a couple of eggs. The sun came up while he ate. It sent golden rays through the trees, caught by the smoke, pollens and insects in the air. He washed his food down with some of his milk. He gave Merlod some more oats, smothered his fire and packed his things. He thanked the river for the fish and moved on with the morning sun at his back.

At midday he sat under an oak tree by the river to rest his aching legs. He ate some venison and drank some more milk while Merlod grazed on the brush. He watched the sunlight glimmer and dance in the rippling current of the river. He thought of the glimmer in his wife’s eyes when he returned home from a deployment, or a hunt, or even a day in the field. She was always happy to see him, as was Gwynette. The girl would squeal and run to him and jump into his arms.

Cwyndher got up. Thinking about Gwynette strengthened his legs again. He took Merlod’s lead and continued. In the evening, he had climbed to the top of a hill. The sun was in his face, streaming through the columns of tree trunks. He dropped his head to keep the dappled sunlight from his eyes. He walked along staring at the ground, with Merlod following his shadow. The stream still babbled alongside them.

Suddenly a person’s long shadow appeared on the ground before him. He stopped and looked up into the sun, trying to shield his eyes with one hand, as his other held Merlod’s lead firmly to keep the spooked pony from bolting. Just in front of him stood a tall man, silhouetted in the lowering sun, his unbleached linen robe set aglow by the evening light shining from behind him.

“Have no fear, good man,” spoke the stranger. His voice was soothing, yet authoritative. “The road you are on is about to lead you into sacred land. None may pass beyond this point without our knowledge and blessing.”

Cwyndher did not let the eeriness of the stranger’s sudden appearance shake him. He squared his shoulders, straightened his back, and stood firm. He cleared his throat. “I’m looking for my daughter. She should be here. Her name is Gwynette.”

“Here?“ The stranger stepped forward so Cwyndher could see him without being blinded by the sun. “Good man,” he said, “I am a priest and a keeper of the Sacred Grove. I have been tending the sacred wellspring for nine summers. There is no one by the name Gwynette in the Grove.”

Cwyndher was now visibly distressed. “B-but she must be! She came here last summer.”

“Last summer? You are sure she came here?”

“Well, where else could she have gone? Is there another sacred site where young people go when you invite them to join the priesthood?”

“Invite them?” the priest repeated curiously and with concern. “What do you mean, good man?”

Worry crept into Cwyndher’s face. “Last summer,” he began in a choked voice. “Several men and women wearing the robes of the priesthood came through our village. They said they were looking for beautiful young people to join them at the Sacred Grove. They chose my daughter as well as some other young women. Surely they came here!”

The priest sighed, and put a comforting hand on Cwyndher’s tense shoulder. “My dear fellow,” he spoke with sincere empathy. “The Keepers of the Sacred Grove are approached –approached, I say- by hundreds of families each spring. All of these families have at least one child for us to consider admitting into the priesthood. We do not choose our members based on their outward beauty, but by their inward glow. We turn away almost every single candidate. We never, ever venture forth to find someone. Good man, we did not come and take your daughter.”

Everything around Cwyndher seemed to darken and fade away. All he could see was the priest’s compassionate face. All he could hear were his heavy words. His knees suddenly felt weak. If not for the priest’s steadying hand upon his shoulder, Cwyndher would have collapsed in despair.

“Perhaps the priests who took your daughter were from another order someplace else.”

Cwyndher shook his head feebly. “They told us they were coming here. They were clear about that.”

“I am sorry,” said the priest. “Please stay here while I fetch my master. Perhaps he will have some advice for you.”

The priest melted into the forest. Cwyndher numbly led Merlod to the river. He kneeled on a sandy bank and washed his face. The cool water took the bewilderment from his mind. Cwyndher wondered about his daughter. Was she alive? Was she hurt? She could be miles away. He may never see her again. He may never know what happened to her. He may never tell her that her mother had died. Cwyndher shed a tear of soulful agony. Then another. Then more.

His tears dropped into the River Daerhi and were swept away. The sacred stream took the tears and all their misery and sorrow and carried them downstream. There, the bubbling and babbling of the water reached the ears of a fairy.

The fairy was lounging on a beam of sunlight listening to the River Daerhi sing its liquid melody. As the farmer’s tears floated by in the stream, the river suddenly sang a woeful song of despair. The fairy started from her rest. She listened intently and also began to weep. Never had the river flowed with such a heartbroken symphony, such lamenting. It was a song of loss. Someone has lost a loved one. A wife… and their child? Yes. A child. The fairy climbed the sunbeams, like steps, to above the forest canopy to listen to the wind. The wind howled all about the affairs of the land. The fairy could learn much from the wind when she wished to do so. The wind told her what she wanted to know about a young woman named Gwynette.

The fairy was curious and caring by nature. She had to find the source of the river-song’s anguish. The fairy ran upstream using the trails of sunbeams. She saw the horse by the river and gave it a fairy’s kiss to keep it calm. She found the farmer kneeling beside the river, his face in his hands. She approached the sobbing man.

“Why do you cry so?” the fairy asked.

Cwyndher looked up towards the voice to see a crooked little old woman, standing in a thicket nearby. Her back was bent and her knees were bowed from age. He wondered how the crone managed to get down to the river and into that thicket without even alerting Merlod.

“Why do you cry so woefully?” she asked again. Her voice sounded young and musical.

The farmer stood. “My daughter, she’s lost. I thought she was here, at the Sacred Grove, but she is not.”

“I can help you find her easily enough. Come with me, I can find her.”

Cwyndher was skeptical. “No, but thank you. A priest is gone to fetch his master to help me. He told me to wait here.”

“Those foolish men!” the crone said. “Mark my words: when the high priest comes here, he will tell you there is nothing he can do for you, and that you must accept the will of the gods, and simply accept your child’s fate, and get on with your life.”

Cwyndher eyed the woman suspiciously for a moment, not even sure what to say. He took Merlod’s lead and went back to the road where the priest had been. The old woman followed him through thicket with ease, despite her aged condition. Finally, the young priest returned with an older priest. This one wore white robes and had a long gray beard.

“My son,” the bearded man spoke, his voice soft and gentle. “I am the high priest of the Sacred Grove. My young brother here has told me of your plight. I’m afraid there is nothing I can do for you. You must accept the will of the gods, for they are all-powerful and all-wise. You must simply accept your daughter’s fate, and move on with your life. I am sorry for your loss.”

Cwyndher was stunned. The high priest said exactly what the old woman had predicted. Then his shock became anger. “What good are gods if they cannot even help a man?”

“That’s what I have always wondered,” said the old woman.

“Mind your tongue!” the high priest scolded. “What do you know of the gods?” He calmed himself. “We have heard of a gang of sinners who roam the hills south of here. They’ve taken over some of the small villages, terrorizing the people. Perhaps they have taken your daughter. If that is so, then you would be wise to let her go. Those are evil men.”

The priests turned and walked into the forest. The younger priest turned back with an apologetic glance.

The old woman smiled. “I know more of the gods than they do. I also know of the wretched men he speaks of. Now, come with me.”

Cwyndher looked curiously at the old woman. There was something about her that put him at ease. He took Merlod and followed the old woman back down the road. The sun setting behind the trees cast long shadows on the road. Soon the forest was dark, the road a faint strip before them, the stream babbling to the night. Cwyndher had thought to stop and make camp, but the old woman kept walking silently and steadily in the black night. Finally, she stopped.

“You shall rest here,” she said. “The horse is weary and hungry. You are too. Rest! I’ll be back.”

The old woman disappeared into the dark trees. Cwyndher sparked a fire and ate some smoked venison. He and Merlod drank from the river. The old woman returned with an armful of apples. She dropped them on the ground. “In the morning, travel down the road the way you came. I will meet you along the way.” She left again. Cwyndher and Merlod ate some of the apples. They were sweeter and juicier than any apple he’d ever had. Cwyndher unfurled his blanket and laid down. He slept restlessly and awoke often. He wondered about the old woman. He has not seen her since they stopped. He thought he should be concerned, but he wasn’t. He felt that there was some otherworldly spirit in her.

Cwyndher did not rise until the sun was sending its morning rays through the trees. He stretched himself and looked around. He found there were more apples in a pile. He ate some of them, and gave Merlod the rest with her oats. Then he packed up and led Merlod down the road. At midday he reached the crossroads and the oaken bridge. The old woman stood there waiting patiently.

She pointed a bony old finger to the road on her left. “Your child is on that road. Go to her.”

Cwyndher looked down the south road. Seeing no one, he turned to the woman. “How can you know this?” he asked her.

The woman smiled and her youthful eyes sparkled. “How can you doubt me after all I have done. Hurry down the road, good man.”

Cwyndher hastily walked down the road. Soon. he saw a young woman running around a bend, her chestnut hair bouncing with her gait.

“Gwynette!” he shouted joyfully. He dropped Merlod’s lead and ran to the exhausted girl. He took her in his arms, laughing.

She clutched him tightly, sobbing. “Papa! Papa!” After a few moments she pulled away enough for Cwyndher to see her face. She had changed; the softness of her youthful face was replaced by hardened stresses beyond her years. Her eyes were wide and filled with torment. She had aged far too much in the months of her absence.

“My child!” he finally sputtered. “I have been so worried! I’ve been so mournful! I tried to find you at the grove, but the priests said you weren’t there. Gods! Your mother has died. I tried to find you to tell you. I’m sorry, child! Momma is gone!”

Gwynette sobbed inconsolably for a while. When her sobs subsided to mere trembles, her father spoke to her again. “What has happened to you? How did you come to be here?”

“Those people which lured me away weren’t from the priesthood,” she began. “They were from a brothel! Instead of taking us upstream, they took us on this road here. They tied us up and dragged us for the whole night. They took us to an old inn. But it wasn’t an inn at all. It was a bordello! Those men wanted us to do unspeakable things, or they beat us! I never did what they demanded, papa! Please, oh please believe me! No matter how they beat me they never got into me!

“One time I escaped, and went to the local magistrate and told him what was happening to me and those other girls, and even young men! He bound me and brought me back there! After that they locked me away in a cell.

“Then last night a sweet voice told me to leave. I said ’I cannot!’ The voice told me not to worry. The door to my cell was always locked, but last night it pushed itself open! The man in the hall who was supposed to be watching me was sound asleep, so I ran! Once I was out of the inn, a swarm of light-bugs showed me the way through the dark until daylight. I ran and ran until I saw you. I could scarcely believe my eyes! Papa…How did you come to be here?”

Cwyndher had nearly forgotten the old woman. “Those priests wouldn’t help me, but this kindly old woman did.” Cwyndher turned to the woman. “You are no old woman. What are you?”

The crone smiled. “You know I am not what I seem. I am called Grac’hed Coz. I am many things. Child, I was the voice guiding you out of the inn while you rested last night. I made your guard sleep so soundly. I was the swarm of light-bugs that showed you the road. At dawn I left you because your escape had been found out. I went back to the inn and stood in front of the men and their horses. The men could not see me, because men generally cannot see what is truly before them. But the horses saw me and refused to go forward. Ha! How those vile men cursed! Little wonder they could not see me with their vision clouded by their evil in their minds! But I could not stay there forever, because life is movement, and I must move. So I came here and made sure you found each other. But make haste! The men chasing you are close now! They mean to kill you. Their horrible secret is too precious to them.”

Cwyndher looked back down the road and listened. He could hear a horse neigh. Then another. Then the ground rumbled. Suddenly five horses rounded the bend in the road, each with an angry and armed rider.

“Gwynette! Run!” Cwyndher said. He planted his feet in the road and faced the riders.

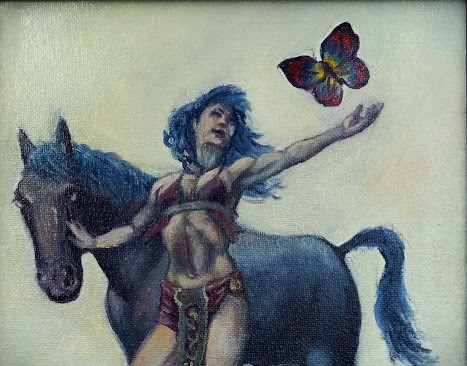

“Allow me to help,” said the old woman who was not. In a flash she went from crone to ageless beauty. A woman of light, she was a being of raw life, unfettered by flesh. Moving with the wind she rushed past Cwyndher and stood before the horses. The unnerved steeds halted in their tracks. One of the riders fell from his saddle with a curse.

“Damned be these horses! They’ve halted again, just like last evening!” The fallen man dusted himself off, and seeing Cwyndher, simply a farmer, standing between them and their quarry, drew a long knife.

The other men settled their unnerved steeds and glared ahead. One of them, who seemed to be their leader, spoke. “Fellow, we have no quarrel with you. Stand aside and let us take what is ours, and you can go home unharmed.”

Cwyndher said nothing.

“Move aside, I say.”

Again, Cwyndher said nothing.

The man who was their leader dismounted and drew a sword. Others in the group followed, brandishing their long knives and axes.

Cwyndher drew his sword.

“That’s a fine blade,” one of the men said nervously.

“So? What of it?” growled the leader.

“Not just any man has a sword like that.”

“Get on him, or I’ll kill you myself.”

The men stepped closer to Cwyndher. They began to form a ring around him.

Cwyndher raised his sword and took a breath. The leader and two other men engaged him head on. The fourth and fifth tried to get past him and go after Gwynette. He furiously stabbed the leader, then slashed to his right, then to his left, then again to his fore.

In seconds, all five of the men were sprawled about in pools of their blood.

He killed all of his opponents. He never took prisoners. He refused to be as cruel as his enemies.

Surrounded by the sliced and bloody corpses of the five men, Cwyndher knelt, panting and aching. He held his left arm, trying to slow a rivulet of blood. The wind blew and the fairy Grac’hed Coz was there. She whispered to his wound and it closed up. In a whirlwind that kicked up the road dust she carried him to Gwynette.

“He will be fine, child,” she said in her musical voice. “See how he smiles at you! You have both made your mother proud. Her life was not in vain. Live your life well!” Grac’hed Coz the fairy floated away on a sunbeam.

“Papa, what of the others? I wasn’t the only one at the brothel, of course. Can we not help them?”

“Hell yes, we’ll help them.” Cwyndher said. “I know a man. A good man. One of my fellow soldiers from the old days. He is a commander near here, with a small battalion of soldiers. We’ll see him and he’ll gladly arrest those snakes and free the others.”

Cwyndher the farmer and his daughter stood over his wife’s grave on the windy hill. He now knew that evil was not confined to the Dracii Mountains. It was all around. As he thought of Grac’hed Coz the fairy, he knew that goodness and kindness were also all around. He held his daughter closely as she let a tear fall down her cheek, this one a tear of joy. As it fell away it was caught in the wind. Cwyndher the farmer heard a musical joyous laugh.